Caught between a rock and a hard place, many ransomware victims cave in to extortion demands. Here’s what might change the calculus.

The recent spate of ransomware payments cannot be the best use of cybersecurity budgets or shareholder capital, nor is it the best use of insurance industry funds. So, why are companies paying and what will it take for them to stop?

Why are so many victims paying ransomware demands?

In simple terms, it may just be, or at least initially seem, more cost effective to pay than not to pay. The current precedent to pay likely dates back to the ethically brave organizations who refused to pay. When WannaCryptor (a.k.a. WannaCry) inflicted its malicious payload on the world in 2017, the United Kingdom’s National Health Service bore a significant hit on its infrastructure. The reasons why they were hit so hard are well documented, as are the costs of rebuilding: an estimated US$120 million. This is without considering the human costs due to the 19,000+ cancelled appointments, including oncology.

Then in 2018 the city of Atlanta suffered an attack of SamSam ransomware on its smart city server infrastructure, with the cybercriminal demanding what then seemed like a huge ransom of US$51,000. Several years on and the reported cost of rebuilding systems is placed anywhere between US$11 million and US$17 million; the range takes into account that some of the rebuild was enhancement and improvement. I am sure many taxpayers in the city of Atlanta would have rather the city had paid the ransom.

With examples of publicly recorded incidents showing the cost to rebuild is significantly more than the ransom, then the dilemma of whether to pay or not may be one of cost rather than ethics. As both examples above are either local or central government, these victims’ moral compasses probably pointed them at not funding the next cybercriminal incident. Alas just one year later the municipalities of Lake City and Riviera Beach in Florida handed over US$500,000 and US$600,000, respectively, to pay ransomware demands.

There is no guarantee that a decryptor will be forthcoming or that, if provided, it will even work. Indeed, a recent survey by Cybereason found that almost half of businesses that paid ransoms didn’t regain access to all of their critical data after receiving their decryption keys. Why pay the demand, then? Well, the business of ransomware became more commercialized and sophisticated on both sides: the cybercriminals understood the value of the data involved in their crime, due to the rebuild costs being disclosed publicly, and a whole new industry segment of ransomware negotiators and cyber-insurance emerged on the other. A new business segment was born: companies and individuals began profiting from facilitating the payment of extortion demands.

It’s also important to remember the devastating effects that ransomware can have on a smaller business that is less likely to have access to expert resources. Paying the demand may be the difference between the business surviving to fight another day and closing the doors for good, as happened to The Heritage Company, causing 300 people to lose their jobs. In countries with privacy legislation, paying may also remove the need to inform the regulator; however, I suspect that the regulator should always be informed of the breach regardless of whether payment was on the condition of deleting exfiltrated data.

Paying is often not illegal

In October 2020, the United States Department of the Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) declared it illegal to pay a ransomware demand in some instances. To clarify, it’s illegal to facilitate the payment to individuals, organizations, regimes and in some instances entire countries that are on the sanctions list. Of significance here is that some cybercrime groups are on the sanctions list. Wasn’t sending or facilitating the sending of funds to anyone on the sanctions list already illegal? I think it probably was, so what was new in this announcement? Oh wait, politics – the voters need to think their governments are doing something to stop the tidal wave of cash to cybercriminals. The European Union follows a similar system with a sanctions regime that prohibits making funds available to parties on the official sanctions list.

Aside from OFAC’s ruling, in the United States there is still no clear guidance on paying ransomware demands, and according to experts it may even be tax-deductible. This may factor into the decision-making process on whether or not a business allows itself to be extorted.

Attribution of either the location or the people behind cybercrime is complex to prove and technology typically assists in assuring that many of these groups remain both anonymous and nomadic, or at least in part. However, knowing who you are paying could be an essential requirement when deciding whether to pay, as inadvertently paying a person or a group that appears on a sanctions list could cause the payee to land on the wrong side of the law. Remember that some individuals on the list may take the opportunity to hide within a group, yet still be sharing the proceeds, possibly making payment illegal.

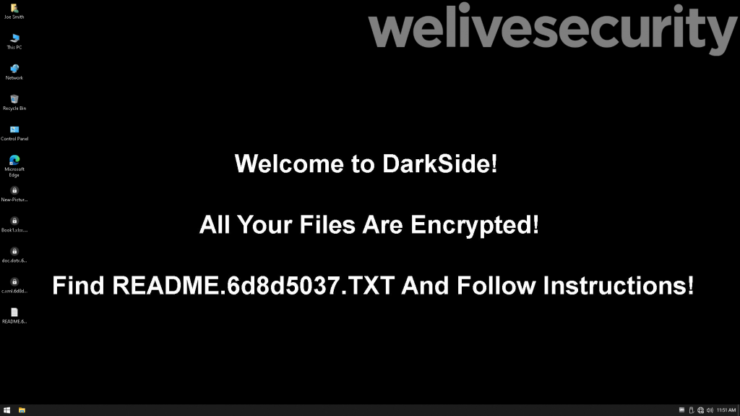

The recent payment of 75 bitcoins (US$4.4 million at that time) by Colonial Pipeline, despite the FBI’s clawback of 63.7 bitcoins (approximately US$2.3 million at the time of recovery, but US$3.7 million at the exchange rate when the ransom was paid), demonstrates that using the sanctions list to prohibit payment is ineffective. Darkside, the bad actors behind the attack and believed to be based in Russia, had been careful to avoid the list by ensuring, for example, that their data storage was not in Iran, thus keeping their “business” in regions that are not on the sanctions list.

The ransomware as a service business model

The cybercriminal group Darkside has now disbanded due to the unwanted attention the Colonial Pipeline incident caused. Was it on the sanctions list and does its closing down mean that the attacks it had in its revenue forecast will stop? “No” and “No”. I am at a loss as to why all known cybercriminal groups are not on the sanctions list, but maybe that’s just too logical. These groups are often service providers and are not the actual attackers who create the “business opportunities”; rather, they provide the infrastructure and services to enable the attackers and then share the revenue generated. This is often referred to as “ransomware as a service” or RaaS, with the actual attackers being commercial affiliates of the RaaS group.

Attackers identify targets, infiltrate their networks in some way, identify and then exfiltrate copies of sensitive data, and then inflict the malicious code from their RaaS provider, such as Darkside, on the victim. RaaS providers facilitate the attack with backend services and the proceeds, once the victim pays up, are then split, typically 75/25. When Darkside quit the business, it’s likely other ransomware service providers benefited and had a bonus day with new affiliates joining with pre-existing qualified deals in the pipeline – no pun intended!

This could raise the question of who is actually responsible for an attack – the affiliate, or the service provider? The attribution reported in the media typically comes from a cyber-forensic team and awards ownership to the service provider, identified by the type of malicious code, payment details, and such like that are a signature and very identifiable. What we rarely hear about is the initiator of the incident, the affiliate; this could very well be that dodgy-looking person down the road, or of course it could be a sophisticated hacker who is taking advantage of unpatched vulnerabilities or a targeted spearphishing attack, and is operating a scalable and well-resourced cybercrime business.

The current trend is to exfiltrate data as well as to deny access to it via encryption; thus, attacks now commonly also involve elements of a data breach.

Is it illegal to pay to prevent data from being published or sold?

The threat that personal or sensitive information may be disclosed or sold on the dark web could be considered a further form of extortion, obtaining benefit through coercion, which in most jurisdictions is a criminal offense. In the United States, where the spate of ransomware demands is occurring, extortion covers both the taking of property and the written or verbal instillation of fear that something will happen to the victim if they do not comply with the extortionist’s demands. The encryption of data and limiting access to systems in a ransomware case is something that has already happened to the victim, but the fear that the exfiltrated data will either be sold or published on the dark web is the instillation of fear in the victim.

With my basic understanding, and I am not a lawyer, it is illegal to make the demand but it does not appear to be illegal to make the payment if you are the victim. So, it’s another scenario where the payment to cybercriminals appears not to be illegal.

Are negotiators and cyber-insurance causing or solving the problem?

The current trend of paying the ransomware demand and an attitude that it’s “just a cost associated with doing business” is not healthy. The question at the boardroom table should be focused on making the organization as cybersecure as possible, taking every possible precaution. With insurance there is likely to be an element of complacency, minimally meeting the need to comply with the requirements set out by the insurer and to then carry on with “business as usual”, knowing that if an unfortunate incident happens, the company can step aside and push the insurer to the front line. The two incidents that affected the cities of Riviera Beach and Lake City where both covered by insurers, as was a payment by the University of Utah of $475,000 and reportedly Colonial Pipeline was also partially covered by cyber-insurance, although at this stage it is unclear if it has claimed.

While cyber-insurance may fund the ransom payment and conduct the negotiation that results in a cushioned impact, there are of course many other costs involved, as previously discussed. The insurers of Norsk Hydro paid US$20.2 million when the company suffered an attack in 2019, with the overall cost being estimated to be between US$58 and $70 million; some of the additional amount may also have been covered by insurance. Hindsight is a luxury, and I am sure that if Norsk Hydro, or any other company that has fallen victim, had its time again it may decide to spend some of the estimated US$38 to US$50 million it then spent above the ransom payment on cybersecurity as a prevention, rather than to cover post-attack expenses to recover from an attack.

If I were the cybercriminal, my first task would be to work out who has cyber-insurance, to narrow the list of targets to those that are highly likely to pay – it’s not their money, so why wouldn’t they? This may be why CNA Financial was targeted and reportedly paid US$40 million to regain access to their systems, and I assume to recover the data that was stolen. As a company that offers cyber-insurance, the significant payment could be viewed as payment not to attack CNA customers as the insurer would end up paying for each attack. This assumes the cybercriminal gained access to the customer list, which is unclear. On the flip side, if an insurer pays up, it would be difficult for them not to pay up if one of their insured clients was attacked – paying in this instance could be sending the wrong message.

Cyber-insurance is probably here to stay, but the conditions the insurance should require from a cybersecurity perspective – a resilience and recovery plan – should define extremely high standards, thus reducing the possibility of any claim ever being made. The insurance must not be allowed to become the fallback option. Attacked? It’s a nuisance but that’s OK … we are insured.

Is it time to ban ransomware payments?

The ransomware attack in May by the Conti ransomware group on the Irish health service could highlight the reason not to ban paying the cybercriminal for a decryptor, and ban payment for them to not publish the data they have exfiltrated. As could the attack on Colonial Pipeline; no government wants to see lines forming at the gas pumps and if not paying means providing no or limited service to citizens, this could be politically damaging. There is a moral dilemma caused by an attack on infrastructure, and paying while knowing the funds are used to resource future cyberattacks is difficult, especially when you consider healthcare.

Paying the ransomware demand also seems to create a second chance opportunity for cybercriminals: according to the survey by Cybereason mentioned earlier, 80% of businesses that pay the ransom subsequently suffer another attack, and 46% of companies believe this to be the same attacker. If the data shows that payment of a demand causes additional attacks, then banning the first payment would significantly change the opportunity for cybercriminals to make money.

I appreciate the argument not to ban ransomware payments due the potential damage or risk to human life; however, this view seems to contradict the current legislation. If the group that launches the next attack on a major health service is on the sanctions list, paying is already illegal; this means that organizations can pay some cybercriminals but not others. If the moral dilemma is about protecting citizens then it would be legal for a hospital, for example, to pay any ransomware attack regardless of who the attacker has been identified as.

Government selection, via the sanctions list, of which cybercriminals can be paid and which cannot, seems to be, in my opinion, not the right course of action.

The cryptocurrency conundrum

As all of you who know me know, this is a topic that causes me to rant and become agitated, both for the lack of regulation and the extreme energy consumption used to process transactions. Most financial institutions are regulated and required to meet certain standards that both prevent and detect money laundering – money gained through criminal activity. Opening a bank account or investing with a new financial organization requires you to prove your identity beyond all doubt, requiring passports, utility bills, inside leg measurements and lots of personal information. In some countries this extends to engaging with a lawyer, a real-estate transaction, and many other types of services and transactions. And then there is cryptocurrency, the Wild West for brave investors and the currency of choice for cybercriminals.

Figure 3. Ransom notes from the Maze, Sodinokibi (aka REvil) and NetWalker groups, respectively (first half of 2020)

There is a level of anonymity granted by cryptocurrency that established a method for demands to be made by cybercriminals and payments to be processed by victims without the disclosure of who is receiving the payment. It’s worth noting that not all cryptocurrencies are equal in this regard, though, with some offering at least a glimpse of the receiving wallet, but not who is behind the wallet, and others even obscuring the wallet itself.

In the last month the confusion of politicians on how the regulate cryptocurrency is clear. El Salvador announced its intention to accept bitcoin as legal tender within three months of the announcement; this would be alongside the US dollar as currently legal tender. However, the World Bank has rejected a request from the country to assist with the implementation, citing concerns over transparency and environmental issues. Coin-mining uses significant energy consumption, and in a world concerned about the environment it is in no way eco-friendly: currently Bitcoin’s energy consumption is the same as the entire country of Argentina.

The Sichuan province in China also cited energy consumption issues and recently issued an order to cease bitcoin mining in its region. This was subsequently followed by the Chinese state instructing banks and payment platforms to stop supporting digital currency transactions. The confusion is, without doubt, sure to continue with countries making unilateral decisions on how to react to the relatively new world of digital currencies.

Cryptocurrency has solved a huge problem for cybercriminals – how to receive payment without disclosing their own identity. It also created demand for cryptocurrency: for every victim who pays, demand is generated to acquire the currency to make the payment. This demand drives up the value of the currency, and the market appreciates this; when the FBI announced it had managed to seize the crypto-wallet and recoup 63.7 bitcoins (US$2.3 million) of the Colonial Pipeline payment, the general cryptocurrency market declined on the news; as the market is a roller coaster, this may just be an eerie coincidence.

Curiously, if you are a cryptocurrency investor and you accept that demand for the currencies is in part created by cybercriminals (which, in turn, drives up the value), then you are, in part, indirectly profiting financially from criminal activity. I recently shared this thought in a room of law enforcement professionals, some who admitted to being invested in cryptocurrency … it created a moment of silence in the room.

Conclusion

This complete disregard for decent behavior and not funding cybercrime by paying ransom demands creates an attitude that funding criminal activity is acceptable. It’s not.

The right thing to do is to make funding cybercriminals illegal and legislators should be stepping up to the plate and going to bat to stop the payments from being made. There may be a first-mover advantage for countries that do pass legislation forbidding payments: cybercriminals that are behind these high-value attacks are focused, funded, resourced, and driven. If a country or region passed legislation that prohibited any company or organization from paying a ransomware demand, then the cybercriminals will adapt their business and focus their campaigns on the countries that are yet to act. If this view resonates as logical, then now is the time to act: be first to push cybercrime to other shores where legislators and politicians act at a slower pace; lobby to make this illegal.

However, in reality, there is probably middle ground to ensure companies that consider paying are not doing so because it’s the easy option. If cyber-risk insurance carried an excess or deductible, payable by the insured, of 50% of the incident cost, and could only be invoked when law enforcement or a regulator is notified, and involved in the decision to make payment, then the willingness to pay may change. If such a regulator for cyber-incidents that required payment existed, we would better understand the scale of the problem, as one agency would have vision on all incidents. The regulator would also be a central repository for decryptors, knowing who is on the sanctions list, engaging the relevant law enforcement agencies, notifying privacy regulators and they would know the extent and result of previous negotiations.

It’s worth noting that a recent memorandum issued by the US Department of Justice places requirements to notify the Computer Crime and Intellectual Property section of the US Attorney’s Criminal Division for cases that involve ransomware and/or digital extortion or a subject that is running the infrastructure used by ransomware and extortion schemes. While this does centralize knowledge, it is only for those cases being investigated. There is no mandatory requirement for a business to report a ransomware attack, at least as far as I know; it is recommended, though, and I would urge all victims to connect with law enforcement; if you are located in the US, this page is a starting point.

If you consider that the revenue generated in the payment of the ransomware demand is illicit earnings from criminal activity, then could cryptocurrency in its entirety be held responsible for money laundering or providing safe harbor of funds directly attributed to cybercrime? Despite its name, governments do not recognize cryptocurrency as a currency; they view it as an investment vehicle that is subject to capital gains tax, should you be lucky enough to invest and make money. Any investment company harboring funds directly gained from criminal activity must be committing a crime, so why not the entire cryptocurrency market until it has full transparency and regulation?

In short, make paying the ransom illegal, or at least limit the insurance market’s role and force companies to disclose incidents to a cyber-incident regulator, and regulate cryptocurrency to remove the pseudo right to anonymity. All could make a significant difference in the fight against cybercriminals.